Three years ago, an excellent report advanced my understanding of which transportation/land use policies can really help to tackle climate change. From all appearances, that report has disappeared beneath the waves without a trace; I’ve met few policy advisors who have read it.

Three years ago, an excellent report advanced my understanding of which transportation/land use policies can really help to tackle climate change. From all appearances, that report has disappeared beneath the waves without a trace; I’ve met few policy advisors who have read it.

The report is Moving Cooler, written by consultants at Cambridge Systematics in 2009. It’s a non-academic technical piece with good math but poor messaging and graphics, and while there was some promotion during the study process, I’ve seen no follow-through. Together, this probably explains why it went unnoticed.

I’ll walk through the report findings in four stages:

- Scope and approach

- What would happen if we deployed a sensible “bundle” of policies all at once?

- How do individual policies compare, within that bundle?

- What about at a “maximum” level? (Discussed in part two.)

My own perspective in this post will be to understand two questions:

- How quickly can we realistically hope to reduce emissions within the transportation sector?

- Which policies offer the greatest potential at a reasonable cost? (This will necessarily ignore other considerations, such as equity or acceptability. To me, the first question is “does it work?” and only then is it worth asking “is it fair?” and “is it politically realistic?”

The report itself was never freely available, but executive summary material and appendices were online until quite recently. As the report website has recently disappeared, I’ve reposted a few of the freely available items for reference:

Scope and Approach

There are three key items to be aware of when interpreting the study:

- The study scope focuses only on policies in two of four areas:

- included: travel activity changes by reducing the distance travelled or shifting to more carbon-efficient modes of travel.

- included: vehicle and system operations by improving traffic flow.

- not included: vehicle technology, such as electric vehicles

- not included: fuel technology, such as cellulosic ethanol

- Confusingly, the “bundles” in the study and the graphs showing potential emission reductions all exclude carbon pricing or fuel taxes or other economy-wide pricing initiatives. These policies are covered elsewhere in the text, but the presentation is quite confusing, especially considering that these are likely the most important policies. I will attempt to cover them more clearly here.

- The study sponsors and steering committee are largely so-called “interest groups” such as environmental NGOs, Shell Oil and ITS America. Surprisingly, this membership hasn’t significantly coloured the study findings or objectivity. The study does not make recommendations and the dry, clinical tone is undoubtedly a requirement for a neutral policy study of this sort with a diverse set of stakeholders.

The study is quite U.S.-centric, but I feel the findings could be easily extrapolated to most English-speaking countries, who have all experienced 65 years of substantial post-war growth in low-density auto-oriented suburbs.

What can a full bundle do?

I’m not going to reiterate what the report itself says well. The executive summary is quite clear; I’ll just add my own interpretation. There are a few helpful points to add regarding the baseline scenario:

- The future fuel prices make sense. I was initially concerned that this 2008-09 study might be too optimistic, as it relies on Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts, which were notoriously optimistic prior to their 2009 release. However, the study clearly tried to grapple with the issue in the absence of EIA guidance and they came up with a fairly reasonable scenario, midway between the EIA’s 2012 “baseline” and “high oil price” scenarios extrapolated out to 2050. That fuel price assumption is essentially $3.70/gal in 2010 with a 1.2% real annual increase thereafter, giving about $6/gal by 2050 (in real dollars).

- The fuel efficiency assumptions are an “optimistic business as usual” scenario, with fuel efficiency improving from 20 mpg to 44 mpg by 2050. This doesn’t include significant policy to reduce gasoline usage through vehicle technology or alternate fuels

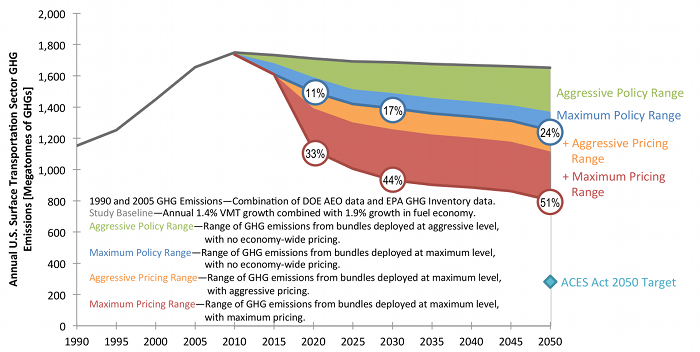

I would characterize the aggressive and maximum scenarios as shown in the above figure (adapted from Figure ES.3). In this figure, I’ve added in the effect of the carbon price / fuel tax policies. As can be seen, this shows considerable potential for carbon reductions from the full policy bundles studied. The key messages:

- Travel activity policies can have a real effect, up to a quarter of transportation emissions.

- Strong carbon pricing of some form must be a part of the mix to make a real dent in emissions; the majority of the reductions shown are due to the pricing policy alone, and the pricing policies have the highest potential early on.

- Additional policies in the vehicle and fuel technology areas are required to hit the long-term reduction targets.

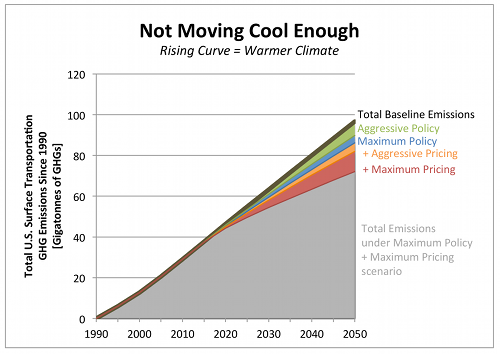

Of course, the climate will continue to change unless we can reach zero annual emissions. Until then, each year’s emissions will accumulate in the atmosphere, adding to the warming. The figure above shows the same information in terms of “total accumulated emissions to the atmosphere between 1990 and 2050.” As long as the emissions curve keeps going up, the climate will keep getting warmer.

What can individual policies do?

The report’s executive summary does a poor job of comparing individual policies or policy categories. I will draw my own highlights instead. Let’s take a look at each policy category and the “best of breed” policy from an emissions perspective, at an “aggressive” deployment level.

| Strategy | Biggest Policy in Strategy | Emissions Reduction (MT) |

Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pricing | Carbon pricing | 4,410 | < $0.05 B |

| Regulatory measures | Speed limit reductions | 2,320 | $6.5 B |

| Systems operation and management strategies | Eco-driving | 1,170 | < $0.05 B |

| Land use and smart growth strategies | Combined land use | 865 | $1.5 B |

| HOV / carpool / vanpool / commute strategies | Employer based commute strategies | 486 | $120.8B |

| Public transportation strategies | Urban transit expansion | 281 | $503.0B |

| Non-motorized transportation strategies | Combined pedestrian | 171 | $30.4B |

| Multimodal freight strategies | Truck APUs | 148 | $0.3B |

| Bottleneck relief and capacity expansion | Bottleneck relief | (5) | $71.4B |

This really says it all:

- Pricing measures are number one, with a bullet. For anyone who’s been around the transportation field for a while, this is fully expected.

- The number two and three measures are probably surprises to many people: speed limit reductions and eco-driving. There’s a reason why Nixon implemented speed limit reductions in the 1970s: they really work at reducing gasoline usage. Eco-driving is also the only effective policy in the “system operations” group (which otherwise consists of ITS road technologies like ramp metering and incident management).

- Numbers four through seven are the usual suspects in “green” circles. But the order may come as a surprise – public transit is a long way down the list.

- Freight emissions are tough: the maximum impact policy is quite small.

- “Bottleneck relief” and “capacity expansion” make the problem worse, not better.

- The top strategies are all quite cheap. The most popular strategies (transit, bottleneck relief) are extremely expensive.

All of this hinges on the underlying analysis, but I feel it’s pretty solid. The appendices of the report give all of the gory details; they’re stellar examples of how to do high-level “sketch” planning. At some point, I’d be curious to try it out with Canadian data; I doubt the results would be very different, though.

Coming next – Part 2

In the next part of this blog post, I’ll look at:

- What does “maximum” deployment look like?

- Concluding remarks

Thanks Dave – very useful. Looking forward to the second installment.