Next: 4 Verification Up: Implementing Baraff & Witkin's Previous: 2 Notation

Baraff & Witkin used condition functions as an indirect way of defining

energy and forces. Their condition functions are almost the same as energy

formulas, since

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the

condition function. For the scalar condition functions (shear and bend),

is the

condition function. For the scalar condition functions (shear and bend),

![]() , and the condition function is hence basically just the

squart-root of the energy, except that it can be positive or negative.

, and the condition function is hence basically just the

squart-root of the energy, except that it can be positive or negative.

The condition functions were defined explicitly in the paper. Energy and forces can also be easily calculated, if the derivatives of the condition functions are known. However, the paper didn't provide explicit equations for the derivatives or second derivatives.

Macri made a good attempt at deriving the equations for the derivatives and second derivatives. I found two major shortcomings in his approach, however. First, he made reference to tensors and other mathematical constructs that aren't really necessary for the derivation. Second, I found an error in his derivation for the bend condition.

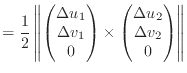

To begin, I will define a few quantities that will help with explanation of

the stretch and shear conditions. These quantities are defined for a triangle

using points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The triangle's area in

. The triangle's area in ![]() /

/![]() space

is given by

space

is given by

|

(1) |

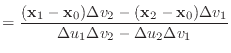

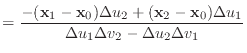

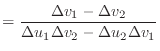

The

![]() and

and

![]() vectors represent the directions of the

vectors represent the directions of the ![]() and

and ![]() axes in world space, as seen within a single triangle. They are defined by

axes in world space, as seen within a single triangle. They are defined by

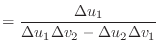

| (2) |

|

(3) | |

|

(4) |

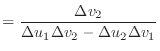

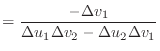

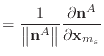

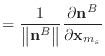

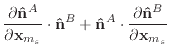

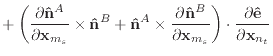

The first derivatives of the unnormalised vectors ![]() and

and ![]() are

given by

are

given by

|

(5) | |

|

(6) | |

|

(7) | |

|

(8) |

|

(9) | |

|

(10) | |

|

(11) | |

|

(12) |

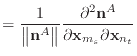

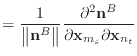

The second derivatives of ![]() and

and ![]() are all zero.

are all zero.

Baraff & Witkin define the stretch condition function as a vector ![]() .

Two special parameters are defined for stretch,

.

Two special parameters are defined for stretch, ![]() and

and ![]() . These

represent the desired stretchiness of the cloth in the

. These

represent the desired stretchiness of the cloth in the ![]() and

and ![]() directions.

A

directions.

A ![]() value below one will result in the cloth trying to compress in the

value below one will result in the cloth trying to compress in the ![]() direction, while a

direction, while a ![]() value above one will result in the cloth trying to

stretch in the

value above one will result in the cloth trying to

stretch in the ![]() direction.

direction.

|

|

(13) |

Baraff & Witkin defined ![]() , the area of the triangle. We define

, the area of the triangle. We define

![]() , for reasons described later.

, for reasons described later.

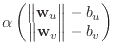

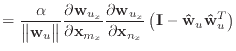

The first and second derivatives of the stretch condition function are

|

(14) | |

|

|

(15) |

|

(16) | |

|

|

(17) |

These second derivatives exhibit some symmetry, since

![]() .

Consequently, the

.

Consequently, the ![]() matrix

matrix

![]() .

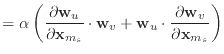

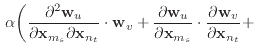

To avoid any tensors when applying Baraff & Witkin's equation (8) to the

shear equations, remember that

.

To avoid any tensors when applying Baraff & Witkin's equation (8) to the

shear equations, remember that

|

|

(18) |

Baraff & Witkin define the shear condition function as a scalar. This

scalar is essentially the dot product of the ![]() axis with the

axis with the ![]() axis in

world space. If no shear is occurring, the axes are perpendicular and the

condition function is zero. If shear is occurring, the condition function is

equivalent to the cosine of the angle between them, weighted by the triangle's

area in

axis in

world space. If no shear is occurring, the axes are perpendicular and the

condition function is zero. If shear is occurring, the condition function is

equivalent to the cosine of the angle between them, weighted by the triangle's

area in ![]() /

/ ![]() space.

space.

Baraff & Witkin's condition assumes that ![]() and

and ![]() are approximately

unit vectors. If

are approximately

unit vectors. If ![]() and

and ![]() are both equal to one, then this approximation

is a fair one. If, however,

are both equal to one, then this approximation

is a fair one. If, however, ![]() or

or ![]() are not equal to one, the

approximation may give rise to some strange behaviour. I have not had a chance

to investigate the effects of varying

are not equal to one, the

approximation may give rise to some strange behaviour. I have not had a chance

to investigate the effects of varying ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

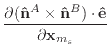

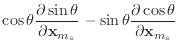

Since we know the derivatives of ![]() and

and ![]() , taking the derivative of

this condition function is trivial.

, taking the derivative of

this condition function is trivial.

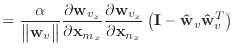

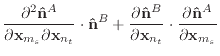

|

(20) | |

|

(21) |

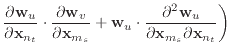

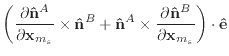

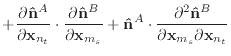

|

||

|

||

|

(22) | |

| (23) |

These second derivatives exhibit even more symmetry than the stretch

condition. Like the stretch condition,

![]() but beyond that, the

but beyond that, the

![]() is actually just an identity matrix multiplied by a

scalar.

is actually just an identity matrix multiplied by a

scalar.

Baraff & Witkin define the bend condition in terms of two adjoining triangles.

I have labelled the unit normals of these triangles as

![]() and

and

![]() ,

rather than Baraff & Witkin's

,

rather than Baraff & Witkin's ![]() or

or ![]() . The unit vector

parallel to their common edge is labelled

. The unit vector

parallel to their common edge is labelled

![]() . Quantities associated with

the normals or the common edge receive a superscript

. Quantities associated with

the normals or the common edge receive a superscript ![]() ,

, ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

|

|

(24) |

| (25) | ||

| (26) | ||

| (27) |

The scalar bend condition ![]() is defined quite simply as the angle between

the two edges,

is defined quite simply as the angle between

the two edges, ![]() .

.

Macri defined ![]() using the

using the ![]() function, which is incorrect and will

only yield positive values for

function, which is incorrect and will

only yield positive values for ![]() . My definition of

. My definition of ![]() will yield

both positive and negative values if implemented using the atan2 function.

will yield

both positive and negative values if implemented using the atan2 function.

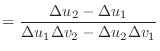

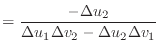

In order to find the derivatives of ![]() , we need the derivatives

of the quantities seen so far. The first and second derivatives of

, we need the derivatives

of the quantities seen so far. The first and second derivatives of

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are shown below, using auxiliary variables

are shown below, using auxiliary variables

![]() . The derivatives of

. The derivatives of ![]() are straightforward to derive.

are straightforward to derive.

| (31) | ||

| (32) | ||

| (33) |

| (34) | ||

| (35) | ||

| (36) |

|

|

(37) |

|

|

(38) |

|

(39) |

Using Baraff & Witkin's assumption that the normal and edge vectors have constant magnitude,

|

(40) | |

|

(41) | |

|

(42) |

|

|

(43) |

|

|

(44) |

|

(45) |

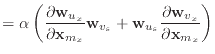

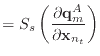

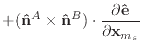

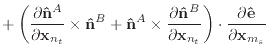

Given the derivatives of the normal and edge vectors, the first and second

derivatives of

![]() and

and

![]() are trivial to calculate.

are trivial to calculate.

|

|

(46) |

|

(47) |

|

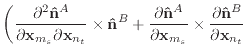

|

(48) |

|

||

|

(49) |

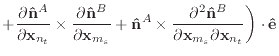

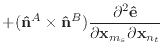

|

|

|

|

(50) |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

(51) |

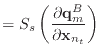

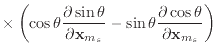

Finally, we can differentiate equation (30) to obtain the

derivatives of ![]() .

.

|

(52) | |

|

(53) | |

|

(54) |

In a manner similar to the stretch condition,

![]() and the

and the ![]() matrix is symmetric. The

second derivatives of

matrix is symmetric. The

second derivatives of

![]() and

and

![]() are likewise symmetric.

are likewise symmetric.