Notes on Hugh McClintock, Planning for Cycling [53]

An excellent book, definitely recommended. It's the first real book dedicated exclusively to bicycle issues that I've found, to be honest. In my view, the best chapters book were those written by Hugh McClintock (1,2,3), the chapter on schools (6), the chapter on integration with public transport (8), and the chapter on Denmark (13).

I've clearly taken a lot of notes on this book. I'll probably take most of them down sometime soon; I think this is a bit excessive in terms of copyright. It's a bit unfortunate really—this book is nearly unknown (I've never seen it cited anywhere), and many new readers could learn about it from a website like this. But such is copyright law, I guess...

The mainstreaming of cycling policy [51]

Cyclists have a difficult position in traffic. ... They are sometimes supposed to follow rules for motorists, sometimes rules like those intended for pedestrians. Their needs are similar to those of pedestrians (short routes, smooth surfaces) but they are taken into account in traffic as a last resort. The situation does not encourage homogeneous patterns of behaviour.

[[62] II. 3.2, p. 29]

The development of UK cycling policy [50]

[29] was apparently a landmark publication in the UK, from a medical point-of-view.

Almost in parallel with the NCS [National Cycling Strategy, UK] preparation of a working party with the DOT [Department of Transportation] involvement, but led by the Institution of Highways and Transportation (IHT) and the Cyclists' Touring Club (CTC), had produced completely updated and consolidated advice on the design of cycle infrastructure to replace that previously produced by the IHT in 1983. This guidance [34] also aimed to consolidate various different sources of advice. It was produced by a working party with wide representation, and tried to discourage too great an emphasis on the provision of special facilities as being the main way of providing for cyclists, relegating facility provision to a lower rank in its preferred hierarchy of:

- traffic reduction;

- traffic calming;

- junction treatment and traffic management;

- redistribution of carriageway space;

- segregated provision (cycle lanes and cycle paths).

The IHT working party was inspired by the comprehensive review of Dutch cycle planning experience published in 1993 [6] and especially its identification of five key characteristics for successful cycle routes:

- attractiveness;

- directness;

- coherence;

- safety;

- comfort.

Reflecting the growing interest in making ordinary streets and roads safer for cyclists and avoiding too much preoccupation with special facilities, the IHT followed up its 1996 guidelines on cycle infrastructure with the publication in 1998 of Guidelines for Cycle Audit and Review [33]. These gave detailed guidance on how cyclists' needs could be thoroughly taken into account in planning any new road or traffic management schemes. The same report also gave guidelines for cycle review, for use in reviewing the cycle-friendliness of existing highway layouts.

[pp. 20-21]

A great deal of useful research work has been done on cycling over the years, particularly in the 1990s by the Transport Research Laboratory (TRL) [63]. Much of this recent work has looked at the newer forms of cycle facility such as contraflow cycle lanes, toucan crossings and advanced stop lines, forms of on-road provision which have tended to be more widely appreciated than some cycle paths and shared paths.

[p. 25]

A "toucan crossing" is apparently just a cyclist-activated traffic signal for a crosswalk, shared with pedestrians. The name comes from the idea that "two can" cross.

There is evidence that, overall, cycling schemes have a good safety record in terms of achieving an overall reduction of 58% in injury accidents, according to data from the TRL's Molasses database [18]. Cycle contraflow systems have a good safety record and are well liked by cyclists, the same report stated. It also commented that advanced stop lines have been found to be a useful facility for cyclists at signalised junctions. However, cycle paths and cycle lanes often have a less clear safety benefit, at least for cyclists. For motorists on the other hand cycle paths may be liked because they are seen as `helping to get cyclists out of the way'. It is particularly irritating for cyclists when they are abused by drivers for not using a cycle path that they know to be distinctly substandard, in terms of route attractiveness, distance, surface or safety—very important perceptions for cyclists [25]—of which passing drivers are likely to be wholly unaware. Cyclists want safe, convenient, attractive and direct access and cycle paths often fail on at least one of these criteria if not several.

The quality of cycle networks should be reviewed, to ensure that all existing facilities do play a net positive role, for less confident cyclists at least. Quality as well as quantity of cycling provision is important and the former needs to be given more emphasis, in initial design and construction and in maintenance. Cycle lanes are often too narrow, encouraging drivers to pass cyclists dangerously [36]. Cycle routes are often fragmented, sometimes leaving cyclists feeling `dumped' at dangerous locations where they most need protection.

[...]

The need to review and upgrade older provision must be explicitly recognised, using detailed feedback from both regular and occasional, and more and less confident cyclists.

Indeed it could be said that there are three basic categories of cyclist: the fast commuter who will tend to ride much more on roads, the utility cyclist and the particularly vulnerable and probably less confident and slower leisure cyclist. Less confident cyclists will tend to give more weight to safety in their choice of route and be more willing to accept detours and longer slower routes while more confident cyclists emphasise directness and speed and generally being able to maintain their momentum. Child cyclists are unable to cope with heavy traffic which more confident commuter cyclists might tolerate for speed and directness. Child and recreational cyclists are more likely to put safety and enjoyment first, rather than directness and speed of journey.

[pp. 28-29]

More sources: [43], [48], [64], [69].

Promoting cycling through `soft' (non-infrastructural) measures [54]

Some of the reasons given for not cycling are exaggerated because of poor perceptions such as people not realising how few days it actually rains in the year, during peak commuting time, compared with their impressions of the number of rainy days. Indeed some surveys have shown how many of non-cyclists' perceptions are exaggerated, when comparing their attitudes with those of a similar group who had had some exposure to cycling [17].

[p. 37]

[Cycling to work and to education ...] Staff are more likely to arrive at work on time, to be more alert when they arrive and to take fewer sick days [29].

[p. 39]

It is also clear from the `after' survey that cyclists are rather less inclined than non-cyclists to express a demand for `more cycle facilities'. By contrast, when asked what further en route improvements they would like to see, cyclists are relatively more likely than non-cyclists to say that they want `better cycle facilities' [11, p. 59], suggesting that experience of facilities is likely to make them more discriminating about quality.

[p. 40]

One survey into the attitude of cycling motorists [42] noted that there are differences between utility and leisure-only cyclists and that someone who cycles only for leisure is not necessarily more likely than a non-cyclist to be encouraged to become a utility cyclist.

[p. 43]

Other refs: [9,13,15,14,32,56,45,59].

Making space for cyclists—a matter of speed? [73]

This chapter was pretty weird, and read more like a rant than an article. Mainly, it's a complaint about traffic speeds in Australia. There was one interesting blurb about an "edgeless" bicycle lane, which sounds similar in principle to San Francisco's chevron markings. I don't think it's as widespread as the author claims, though.

In Australia, a bicycle symbol has been used as the standard graphic, e.g. in bike lanes. The standard symbol is typically 1.15m wide and thus ideal for identifying where cyclists are expected to travel on the road. By use of a series of symbols along a road, with location selected to suit the traffic speed, speed limit, parking and other road requirements, a zone or bicycle lane without edges is created. [...] The concept of a bike lane without edges may initially appear controversial. However, if the intention is to share the road while creating space for the bicycle, it is the edge line of bike lanes which creates the division and the potential for territoriality and the resulting claims of ownership and trespass whether it is cyclists moving out of the bike lane or motorists driving into it.

[p. 58]

Refs: [72].

Homezones and traffic calming: implications for cyclists [65]

The orthodox view had grown, in thinking about traditional areas in the Netherlands, that the street was only for passage and, by default, for motor vehicle movement and increasingly for motor vehicle parking. The Dutch have overturned this perception with the homezone and have re-created the street as a social space, as a place for play and a place where walking and cycling could again be safely enjoyed. The important lesson for cycle policy is that these social streets are attractive for cyclists and their arrangement, their layout, has been reproduced in modern Dutch planning to a great extent. The Dutch often quote Buchanan's Traffic in Towns [57] as a stimulus for their development of environmental areas separate from the main traffic streets. The contrast with British policy is dramatic, however, in that the functional hierarchy pursued in Britain has effectively focused the residential areas into tightly bound `islands' whose separation from each other and from other facilities has encouraged car use and curtailed walking, cycling and public transport.

[pp. 72-73]

[T]he current aim, the Dutch `Sustainable Safety' policy, is for all residential areas to be reconstructed to the 30kph standard by 2010 [58].

[p. 74]

The parking provision for De Dijk [1998 housing development of 1360 dwellings] is built at 160%. Each house has a built-in garage giving 100% with the balance of 60% parking provision in publicly shared, road centre spaces or spaces at the end of the street at the edge of the area. Within a short time of the housing being occupied about half of the garages were being used as storage, so the on-street parking was under pressure. [...] The two way single carriageway [in Liseiland section] opens into a single lane `dual carriageway' area with road centre play space, planting and parking, around 12-14 metres generally. These dimensions mean that it is never easy for cars to pull into garages, sometimes requiring more than a three-point turn in the scant 5 metres available.

[pp. 80-81]

Developing Healthy Travel Habits in the Young [8]

First was the study by Mayer Hillman et al [30] of the travel habits of 7-11 and 11-15 year-olds over the period 1970-1990. The authors found that there had been a significant loss of independence, coupled with a growth in car dependency and a disquieting fall-off in equipping children with the skills to become confident and independent travellers later in life. Then, pioneering researchers into children's travel actually started to consult the children themselves on their needs and desires—and found a marked mismatch between what adults perceive to be `best' for children and what the children would really like. Ironically, parents had drifted into a vicious circle: an understandable desire to keep their children safe led them to ferry them everywhere by car, so creating less safe conditions for children to travel by other means. On the other hand, researchers generally found that children want to explore their capabilities and environment, for example by walking and cycling.

[p. 86]

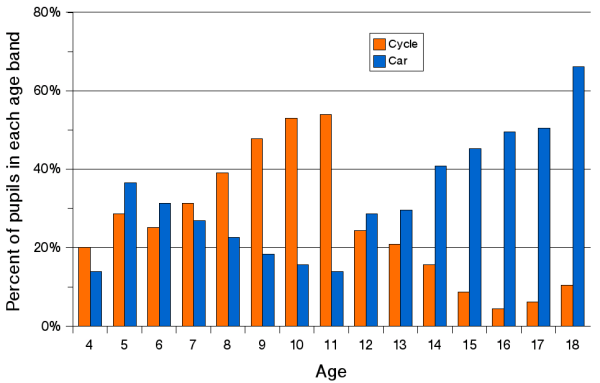

[T]he views of 27,000 pupils were canvassed to determine how they travelled to school—and how they would prefer to, given a completely free choice. The results were enlightening: around a third of all pupils would prefer to cycle to school, with figures as high as 54.5% for 11 year-olds; currently, fewer than 2% do so [61].

[p. 88]

[p. 89]

To avoid any possibility of a school being held legally liable in the case of an accident to a pupil quite a number of schools strongly discourage or even ban pupils from cycling to school. Only in late 2001 was official advice issued that schools could not legally prevent pupils cycling to school, although they had no obligation to allow bicycles on to school premises nor to offer secure or indeed any cycle parking facilities.

[pp. 95-96]

Refs: [67].

The UK National Cycle Network: a millenium project [24]

A good breakdown of costs (about 200 million pounds total) for the UK cycling network on page 105, taken from Sustrans.

Cycling with public transport: combined in partnership, not conflict [31]

In the UK there is a perceived need also for arrangements to adjust from cycling to working, which may require showers and dedicated changing facilities if the journey is likely to involve great exertion. These are rarely demanded by European utility cyclists, who tend to ride bikes (with integral weather and dirt protection) at a leisurely pace in the clothes they will be working in.

[p. 113]

Not all cyclists can store their bikes safely and conveniently where they live. This tends to be more of a problem in cities and student accomodation, where a large proportion of the population live in flats [44] with no separate garage space. Work by the author with the City of Edinburgh Council on tenement cycle parking, where bikes can obstruct stairways and passages, where no formal options are offered, found one user who cycled less because her current flat was 200 m from where she could secure her bike.

[p. 113]

[B]ikes left regularly in the same place [at bike/transit interchange points] for long and predictable periods are a prime target for theft and vandal attack.

[p. 115]

Dutch transport policy is now looking to increase the role of the bicycle at the expense of some bus trips for distances of up to 5 kilometres [70]. In that densely populated country, 60% of all trips by bus, tram and metro are of this distance or less. Official thinking now regards these short trips as determining the capacity required during the rush hour and also that they cause a major part of public transport operators' losses.

[pp. 115-116]

Many Dutch people also use a bike when they complete their rail journey, to go on to their destination, according to a survey by Brachet et al [3, p. 88]. This kind of travel habit, bike-ride-bike or `sandwich' travel, is also very common in Denmark, with people often reducing the risk of theft of the bicycle left at the destination station by leaving an old bike there and keeping their best bike at home, for home-based trips.

[p. 116]

- The Dutch Fiestparkeur bike rack standard is a good model with well-chosen dimensions (p. 117)

- long-term contracts are usually preferable for lockers, to avoid coin-operation and ensure that users are traceable (p. 120) for security reasons (pp. 119-120)

[S]everal management regimes [for cycle parking] have shown levels of security which allow the site operator or hardware supplier to carry the liability for loss or offer very low cost theft cover. This issue is vitally important for the valuable core business generated from regular commuters, who leave bikes for long periods on a regular basis in the same location.

[p. 118]

The Swiss tradition has even greater coverage [68] where Swiss Railways, SBB/CFF, introduced cycle hire in the 1950s as a service for travelling salesmen. In recent years demand at Swiss stations has grown steadily, with the growth of leisure.

By 1991 cycle hire facilities were offered by no less than 600 Swiss stations, this is, most stations in the country [23], but the dominant operation is now branded as Rent-a-bike with 250 outlets in Switzerland, and 120 in Austria. The Japanese have gone further to handle the major demand for cycle access from the station to final destination, and have fully automated dispensing `towers' [26], which deliver a fits-all utility bike, when a user swipes their stored charge card to debit for a bike hire. The consideration of free bikes is one which should not be taken lightly. There is a history of failure in achieving a scheme through which the bikes can be maintained and users made responsible for their return.

[p. 122]

Informal cycle parking at any location is a good indication of demand—as are NO BIKES signs.

[p. 123]

The bike really begins to show its benefits in outer suburban areas, and a range of up to 2 kilometres is generally considered acceptable. In the UK this can be seen from travel patterns for the stations on the main London-Southampton rail line, where there are very high levels of cycle use at stations like Woking. Here th catchment is large, users benefit from riding further to a better-served station, and the cycle access and parking enable a more direct route to the train. The option is aided by a greater preponderance of relatively spacious one family houses, with garages and often garden sheds, making it easy to store the bikes. On this basis, encouragement of bike-and-ride can increase tenfold the catchment areas of local stations [3].

[...]

The Woking effect shows how demand for cycle parking at particular stations can also be influenced by the fare zone structure operating in certain city-wide or conurbation transport systems. In a further example, from Zurich, it has been observed that there is a heavier demand for cycle parking at the last station within a particular fare zone, as people use their bikes to make a rather longer trip to catch their train, rather than go to a nearer station and pay a higher fare!

[p. 123]

Die Bahn (DB) (German Railways) has seen a healthy return on accommodating cyclists, for a fee, on all trains, and carries details in English on their website. Similarly SBB/CFS/CFF (Swiss Railways) have experienced massive growth in international bookins from passengers with cycles.

[...]

The enlightened attitude of DB has led to co-operation with the ADFC (German Cyclists' Club) in producing a report following their research into the most suitable designs of train for cycle carriage. This concluded that, apart from special accommodation on popular tourist routes, or four large parties, the ideal option is to stack bikes on supporting systems along the sides of a coach, where the seating can be folded away (or tips up) when not required.

[p. 126]

The nature of operation of some routes allows the use of a special `bike-and-ride' tram trailer, for carrying up to 25 bikes, that can be rented by groups at weekends on [Basel, Switzerland] tram line 10 which runs out into the nearby attractive countryside of Alsace. The use of old tramcar chassis for special vehicles is an option only available on the older networks, where such fully depreciated but serviceable vehicles are at hand.

[...]

New systems and those where modern vehicles require the traction and coupling systems to be compatible are less like to offer this facility. In Germany the carriage of bikes on trams has faced more prohibitions but is now becoming more common, and not just outside peak hours [3]. New vehicles on demonstration, as shown by Siemens in Barcelona in 1997, even include a bike carrying space designed in.

[pp. 129-130]

The major issue affecting cyclists is not the parking and access to tram stops, or the on-vehicle facilities, but the interaction between the cyclist and the tram tracks where there is on-street running. On-street running of trams has traditionally been feared by some cyclists who worry about getting their wheels caught in the tracks [16] but this is not the way in which a cyclist is brought down. Essentially the railhead and flange guide offer narrow and smooth surfaces of a width comparable with the maximum acceptable for tar banding, another slippery surface when wet. Cyclists will instinctively seek a path that crosses an irregularity such as a dropped kerb, or any street ironwork, including tram rails, with no side thrust on the contact patch between tyre and road. In designing a new system the on-street sections need a rigorous safety audit to eliminate such hazards.

The danger is thus greatest where cyclists cross rails at an acute angle, and reports from Sheffield and Croydon, where extensive street running takes place, highlight a very limited number of locations where practically all falls take place. Sheffield casualties have been analysed [5]. By comparison the Metrolink, Birmingham and Blackpool systems, with very limited on-street sections, tend to have casualties where the tram lines cross the main traffic flows. The potential for risk is thus much reduced, as casualty rates show.

The flangeway also can grab a tyre or retain leaves and other debris which will `lubricate' the adjacent surfaces. The proper tramway rail profile is, however, preferred to the assembly of check rails and infill, but Corus—the UK supplier of most rail profiles—advises that some categories include special preparation of the rail to limit flange squeal (i.e. greater slipperiness) and a bonded polymer fillet which compresses to form the bond between the road surface and track. The necessary gaps at point blades and frogs are further details to keep cyclists clear from.

Observing the standards for installation it is noted that HSE (Health and Safety Executive Railway Inspectorate) set a tolerance for rails to be flush with the road surface, or up to 6 mm above it. In Freiburg where there are high levels of cycling, the rails tend to sit slightly below the road surface, allowing the rail to be bridged by the tyre contact patch, which is then more likely to be bearing on the higher friction road surfaces on either side.

In Freiburg there is also regular flangeway cleaning which removes debris that will create slipperiness for both the cyclist and the tram, as it is displaced or washed out onto the railhead. A further issue is the monitoring of railhead wear, as the flange guide will gradually end up sitting above the railhead with a narrow edge which will act like a machinery skid on any items rested on it. Evidence to date is that there is no closely managed regime to monitor and maintain the track profile. Even if one existed, there is a risk of divided responsibility for maintaining the rails (operator) and maintaining the road surface (roads authority). The interface between the two seems to escape any attention or responsibility for its condition.

A number of proprietary street track units to offer a soft infill for the flangeway, but this does not hold up for regular use with speeds above a slow crawl. These do not last in use on a transit system—as evidenced in several US cities. Fundamentally the design of areas where cyclists meet with trams and tram tracks should either provide a direct crossing of the track at a safe angle, or provide sufficient road space for the cyclist to take a suitable line through the hazard. Sheffield's most notorious location puts the cyclist in a position on the carriageway where they cannot easily claim space to swing out and across the rails, and are thus forced to cross at an unsuitable angle.

Toronto's system has a large number of routes and resulting `turn-backs' in the Central Areas as lines criss-cross the grid system of streets. Strong enforcement of parking bans at junctions and the functional concrete slabs along the outer edge of the rails provides a space for cyclists to pull to the right, and avoid hitting the turning rails at too shallow an angle. A zone of differing colour and texture, which defines the swept path for parked vehicles to observe, and reminds the cyclist that they are about to cross a tram rail, if they stray further, is very important.

[pp. 130-133]

In Denmark it is compulsory for taxis to be able to carry a bicycle, and in Germany it is common in some very hilly places for cyclists to ride their bikes downhill and, when going uphill, to take their bikes by taxi!

[p. 137]

Other refs: [12,19,20,22,27,41,39,47,60,]

Planning for more cycling: the York experience bucks the trend [28]

At the heart of the strategy lies a hierarchy of road users which was (and still is) used to guide both design and funding priorities. The hierarchy (now slightly modified) is set out below:

- pedestrians;

- people with mobility problems;

- cyclists;

- public transport users (includes rail, bus, coach and water);

- powered two wheelers;

- commercial/business users (includes deliveries and HGV);

- car-borne shoppers and visitors;

- car-borne commuters.

[p. 144]

Also in the central area, but outside the footstreets, is the River Ouse. This has three bridges all of which are available to all traffic and which are very busy. Cyclists have not been specifically catered for on these bridges due to the lack of available width. This means that in crossing the river, cyclists have to mix with general traffic. A recent scheme which recognises this and conforms to the council's policy of promoting cycling is on the Skeldergate bridge—one of the three central bridges. Until recently this bridge had a two lane approach to traffic signals at one end. One of the general traffic lanes was removed to allow the introduction of a dedication cycle lane on the approach to the signals for cyclists turning right and a lane which allows left turning cyclists to bypass the signals altogether. This had inevitable consequences for the traffic capacity of the signals leading to much greater queuing on the approach to the bridge. However, several months later this has now been accepted by the motoring public and has huge benefits for cyclists. This is typical of the approach now being taken to help cyclists. At many locations the only way to provide meaningful help for cyclists is by reallocating road space away from motorised traffic. A piecemeal approach has been taken to avoid an outcry from motorists which would be likely to result if many such schemes were introduced at the same time.

[p. 147]

[A] system, and staff, dedicated to highway maintenance are not physically well equipped for cycle route inspection. Often urgent attention is needed but on a very small scale. For example, if broken glass is reported on a cycle path, it needs to be dealt with the same day. To employ standard highway maintenance staff and machinery is very difficult.

Over the last few months a new system has been set up which has had a profound beneficial effect on network maintenance and illustrates how the scale of the operations needs to match the scale of the task. Two part time rangers have been employed who are dedicated to cycle path maintenance. Between them they patrol the entire off-carriageway network using bikes equipped with trailers and hand tools. This enables them to carry out all day-to-day maintenance including cleansing, removal of broken glass and control of vegetation. They are also able to report more major problems to the highway maintenance team. The rangers have a high profile due to their trailers and high visibility clothing which means that users are aware that the maintenance issue is being taken seriously. It is now intended to equip the rangers with mobile telephones so that they can respond even more quickly to complaints and also contact the appropriate authorities in the event of any misuse of the network.

[p. 151]

Planning for cyclists in Edinburgh

Nottingham [52]

An efficient means of transport: experiences with cycling policy in the Netherlands [71]

When the ministry wanted to know why there is more cycling in the Netherlands than in surrounding countries, and why there is more cycling in one city than in others, it realised that research on the history of bicycle use and bicycle policy in a number of those countries was necessary. This research was carried out because we were hoping that we would be able to use the lessons from the past for future policy. On the basis of the results the following statement can be formulated: `Bicycle policy can be effective, but it does require patience.'

To explain this statement, first some frequently mentioned factors that influence bicycle use in the Netherlands have to be discussed:

- Topography. The general impression is that the Dutch cycle a

lot because they live in a flat country. This flatness of course plays a

part, but apparently it is not the only precondition; people living in flat

areas outside the Netherlands cycle much less.

- Spatial structures, town and country planning. These are

influential. This may explain why there is little cycling in the USA and

Australia, but in many European countries the average trip distances are

fully comparable to those in the Netherlands. Nearly 70% of all trips in

the Netherlands are 7.5 kilometres or shorter.

- Availability of alternative modes of transport. Mass

motorisation got started quite late in the Netherlands. However, there are

now about 400 cars per 1000 people. That comes down to one car for every

two persons aged 18 years or older. Still, the number of trips of 7.5

kilometres or shorter is the same for cars and bicycles. As for public

transport, most cities in the Netherlands are too small for profitable bus

and tram traffic to be an efficient alternative to the bicycle. The train

as a mode of inter-local transport is hardly competitive with the bicycle.

- Cultural historical values. That these play a role is illustrated by the choice of transport mode of Dutch people of Turkish, Moroccan and Surinam origin. They cycle much less and use public transport more often. The differences with people of Dutch origin, however, seem to be decreasing with each generation.

These four factors—topography, spatial structure, available alternatives and cultural historical values—do not sufficiently explain the differences in bicycle use between the Netherlands and other countries and between one Dutch city and another. Neither do they explain why bicycle use during a certain period of time increases considerably in one city while it sharply decreases in another.

Additional answers can be found when looking at the influences of policy. What is policy, however? What is bicycle policy? Policy can be taken as comprising the government's intentions and—more important—actions that go with those intentions.

[pp. 194-195]

[I]n the period between 1990 and 1997 about €176 million (£109 million) in government subsidy was given to local authorities. To be clear, the total amount spent on bicycle traffic infrastructure during this period in the Netherlands is estimated at €930 million (£577 million). As a result, the total length of cycle paths has increased by more than 4000km, an increase of 25% compared to 1988. This does not seem to be very much, but it is especially important that a lot of attention was given to the quality and the safety of all bicycle facilities, including the existing ones.

[p. 200]

[S]erious accidents involving cyclists are largely related to collisions with motor vehicles. This is the result of differences in mass and speed. There is not much that can be done about differences in mass, but there is something that can be done about the differences in speed. Sustainable safety with regard to bicycle policy can therefore be translated into three simple rules:

- Encounters of high speed car traffic and cyclists should be avoided. This means separation: in terms of place (such as separate bicycle paths), time (such as with traffic lights) or accessibility (no cyclists on motorways and closing off shopping areas to car traffic),

- If separation of high speed car traffic and cyclists is not possible, there is only one solution left: drastically reducing the speed of car traffic, through any measure whatsoever,

- Simplifying traffic situations. The more complex the situation, the more problems traffic participants have. Novice traffic participants especially can benefit from this—children who are learning to cycle, young adults who are learning to drive a car or motorcycle. Elderly traffic participants will also benefit from simply traffic situations. Research has shown that they do not make more mistakes in traffic, but they do need more time to take all kinds of decisions. Especially in complex situations there is simply no time. And that is when elderly people have problems.

[pp. 204-205]

In September 2001 even the Dutch Minister of Transport was heard to say that she would not think of obliging cyclists to wear helmets. She expects that a lot of Dutch people would ignore such an obligation. And if people did wear them, she is afraid that this would drastically reduce bicycle use. [...]

And do these helmets provide any real advantages for cyclists? If you fall on your head, yes. But not so much if you are hit by a car driving at 50 or 80km per hour. So helmets mainly have a positive effect in accidents that are less serious.

[p. 205]

Target: a substantially lower number of bicycle thefts in 2000 than in 1990. Unfortunately, this target was not reached. The annual number of bicycle thefts has remained at an even level for the past 15 years, at between 600,000 and 700,000 thefts a year.

It is extremely difficult in the Netherlands to find a solution for bicycle theft, one of the main obstacles in promoting the use of bicycles. A good start was made with the improvement of bicycle parking facilities in such a way that they provide better protection against bicycle theft. But we still have a long way to go before the effects of all those improvements become more visible in the streets.

[p. 207]

For the next seven years, the Ministry of Transport has allocated about €210 million (£130 million) to be spent on improving and expanding parking areas and facilities for bicycles, in and around railway stations.

[p. 208]

German cycling policy experience [2]

As shown by a recent Danish investigation too [35], the accident risk for cyclists decreases in the North-Rhine-Westphalian towns when the number of cyclists increases [21]. A large number of cyclists may create more awareness of their presence by other road users. In addition, in the towns with more cyclists the cycle networks tend to be better developed.

[p. 216]

The survey mentioned above worked out an adequate number of parking facilities for different buildings' uses. Some results are:

- For office use purposes and office-type service use purposes demand is determined by the proportion of employees who use bikes and by the number of customers using bikes.

- For retail trade use the following differentiation can be made:

- small shops for daily requirements,

- retail outlets under 1200m2 in area selling, e.g., clothes or books,

- retail trade supermarkets under 1200m2 in area and

- retail trade in larger areas.

- Large scale leisure facilities with catchment areas extending beyond local requirements, such as cinema centres, have a considerably lower demand than local-orientated leisure facilities.

- The proportion of people using bicycles among building users can be

influenced by

- the location of a building in the urban area,

- the provision of motor vehicle parking spaces,

- the quality of the local public transport connections, and

- the topography.

[p. 218]

Urban cycling in Denmark [40]

A factor contributing to the high level of cycling is the relatively low level of car ownership in Denmark. On average there are 347 passenger cars per 1000 people. Car ownership in Denmark is therefore still low compared to its neighbouring countries, the main reason being the rather high taxation on cars. The difference is, however, diminishing due to a general increase in Danish incomes, which has resulted in a significant increase in the number of cars in Denmark over the last 15 years.

In parallel to the increase in cars there has—with some exceptions—been a decrease in the use of bicycles since the mid-1980s. Several studies indicate that the main reason for this is that Danes are normal, lazy people: once the car is there, it is very easy and tempting to use it, and the bicycle is left at home even on short trips, where it would serve as a quick and healthy alternative. Furthermore, the general perception of what is safe and responsible behaviour has made many people transport their children to kindergartens and schools by car.

There are, however, interesting exceptions to the trend. In the central area of Copenhage, for example, there has been a more than 100% increase in cycle traffic over the last 25 years, the increase being greatest over the last 10 years, where a significant increase in car ownership and use has also been found. In Odense as well cycling has increased. Car ownership in the central municipalities of Copenhagen and in Odense is 223 and 303 per 1000, respectively.

The positive trend for cycling can be attributed to the efforts to promote cycling carried out by the municipalities in question. The municipalities of Copenhagen and Odense have both been active in the area, by providing infrastructure and by various campaign initiatives. Odense was appointed `The Cycling City of Denmark' in 1997 and granted financial support from the Danish government to carry out various experiments over a five year period in the field of promoting safe cycling.

Positive measures for cycling cannot, however, in themselves explain the positive development of cycling in Copenhagen and Odense. Other important factors are car restraint measures such as car parking charges, car parking restrictions and restrictions on car access to the city centre. Rush hour congestion, where streets are still passable by cyclists (especially where cycle tracks are available), as well as slow or deficient public transport alternatives, also contribute to the popularity of the bicycle. In terms of time and economy the bicycle is highly competitive in the city centres, and is therefore used.

[pp. 223-224]

In Denmark, the principal type of cycle facility is the cycle track, which is not commonly found in North America. From what I've seen, they are grade separated (i.e., higher than the roadway, with a curb separation; sometimes lower than the sidewalk though). They are usually immediately adjacent to the road, with no trees or sidewalk furniture between bikes and the roadway. This keeps them relatively visible to drivers. Parking is usually between the cycle track and the roadway, reducing conflicts with parking cars. Parking is usually dropped well before the intersection, and the cycle track is lowered onto a conventional bicycle lane at road level. This makes bicycles visible to motorists at the intersections, avoiding some of the common problems with segregated facilities. Cyclists typically have priority over right-turning motor vehicles, using a recessed stop line for motor vehicles or separate signalisation.

While I haven't seen these in operation, I really like the concept; I think it's the best design I've seen. Vancouver is preparing to implement its first bikeway in this model: the $5 million Carrall St. Greenway. The only shortcoming of the Carrall route is that pedestrians are allowed on the cycle track.

The reason for making cycle tracks was in the beginning to increase the comfort of cycling, giving an alternative to the normal street surface, which consisted of cobblestones. Later, in the 1930s, cycle tracks were constructed in order to organise the different means of transport on the streets. One could also say that this was done to get cyclists out of the way, so that cars could go faster. Older pictures from Copenhagen show how cars could be trapped within a flood of cyclists.

[p. 225]

Since 1950 the main reason for making cycle tracks has been to make safe conditions for cyclists. So far as comfort is concerned, the cyclist is today quite often worse off with cycle tracks compared to using the road, because of too little attention being paid to the need for cycle track maintenance. Another challenge is represented by the extended use of granite for redesign of urban streets. Often the cyclists' need for even surfaces is forgotten in the strive for aesthetic solutions.

In general, however, cycle tracks serve the needs of cyclists very well, and are usually the backbone of the cycle network in Danish cities, enabling cyclists to use the major urban streets safely and comfortably. Cycle tracks are also very popular. Among planners as well as ordinary people they are believed to be a precondition for cycling. It is even generally believed that a full separation of motorised and non-motorised road users is the ideal solution. Apparently the obvious way forward, such a concept was developed under the headline `The SCAFT principle' in the late 1960s and employed to a great extent for the construction of new urban agglomerations in Denmark from the 1970s onwards. So far the results have not been better than before. Fully separated path systems are fine for children going to and from school. Usually, however, the paths are felt to be socially unsafe and confusing with lots of detours compared to the road system, resulting in people walking and cycling along the roads where this was not intended. This is very similar to the experience of Milton Keynes in the UK.

Planners today tend to believe more in integration of cars and bikes where car speeds can be kept at a moderate level and, where car speeds are higher, separation with cycle tracks.

[pp. 225-226]

Research has shown that the safety problems at junctions and roundabouts generally are associated with motorists failing to watch out for—and give way to—cyclists. The urban traffic situation is very complex, and a `new' element such as the cyclist is difficult to take into account. This was especially demonstrated in connection with some of the cycle tracks constructed in the 1970s and 1980s. It came as a major surprise when such cycle tracks, built to make cyclists safer, actually resulted in an increased number of accidents at junctions.

The lessons learned are that it is very important to give all classes of road user the best possible opportunities to watch out for each other:

- There should never be a verge [median, separation] between the road and the cycle track close to the junction.

- For at least the last 30 metres the road and cycle track should be directly alongside each other, if possible with no difference in level.

- The stop line for cars should preferably be five metres behind the one for cyclists so motorists will not overlook cyclists when both are waiting at red lights.

- The extension of the cycle track should, at least at big junctions, be clearly marked with a distinctive colour and bicycle symbols repeated through the junctions.

Another important lesson is that the safety of cyclists improves as the number of cyclists increases. This is closely linked to the attention paid by drivers—if there are many cyclists, car drivers will more easily remember to look out for them.

More recently, retarded stop lines for drivers and blue cycle lanes in the bigger junctions have become widely used. Quite often one will also find that a cycle lane some 30 metres before the intersection ends in a combined lane for cyclists and for cars turning right. Cyclists do not necessarily feel much safer as a result of this measure, originally introduced to increase capacity, but it tends to be quite safe in terms of accidents between cars and bikes.

Roundabouts still represent a serious challenge so far as the safety of cyclists is concerned. Roundabouts with two parallel car lanes are especially problematic. In a number of cases the cycle track has been removed from such roundabouts, and cyclists have instead been obliged to give way at all entry and exit lanes, meaning that the passage through the junction becomes very annoying and time consuming. A much better, but far from cheap, solution is to separate cyclists and motorists in two levels at such roundabouts. A number of such roundabouts are found in Denmark.

Some 12% of the total road network in Denmark is equipped with cycle tracks. Taking into account that a large part of the network consists of residential roads and rural roads with low traffic volumes, this means that a major part of the most important urban streets have cycle tracks. This is despite the fact that the construction of an urban cycle track along both sides of an existing street is rather expensive, costing DKK 3-6 million (€0.4-0.8 million or £0.25-0.5 million) per kilometre.

[pp. 227-228]

A really innovative [activity in Odense] has been the installation of a row of small light posts along a cycle track helping cyclists to avoid stopping at a red light—the world's first green wave for cyclists.

[p. 229]

Cycle tracks are found along almost all major streets [in Copenhagen], the width usually being at least 2.1 metres. There are 307km of cycle tracks and 10km of cycle lanes in Copenhagen, which means that more than 42% of the total road network of 378km is equipped with cycle facilities on one or both sides. On top of this there are 43km of green cycle routes.

In order to make fast progress towards having all major roads supplied with cycle tracks, cycle lanes have been established as an intermediate solution along the roads where cycle tracks are planned but not yet built. In contrast to the cycle tracks, which are separated by a kerb and a difference in level, the only separation between cycle lanes and the motor traffic is a white line. Cycle lanes have been shown to be quite effective, in spite of not giving the same degree of safety as cycle tracks. They are to a surprising degree respected by motorists. [Accompanying figure shows a lane, but parked cars separate the bike lane from moving vehicles. It seems to be a contraflow lane too, so parked drivers face oncoming cycles.]

As a supplement to the cycle track network a plan for a network of high level cycle routes has been developed. The routes will be designated to enable the cyclists to go fast with as few stops as possible. Altogether the length of the planned route network is 100km. Part of the network will make use of already existing roads or paths; the remaining 62km has to be built from scratch. The network will be constructed to a high standard and the implementation of the plan is estimated to cost about DKK 500 million (€70 million or £40 million).

[pp. 231-232]

The municipality is using a special tool—the so-called Bicycle Account—to follow the development of the plans and monitor the situation. Hard figures about the route network and the number of accidents as well as figures about the user assessment of a number of issues are included in the Bicycle Account. Other issues covered are the cycling and traffic policy of Copenhagen. The Bicycle Account is produced every two years and has been published since 1995.

User surveys have revealed that 60% of city cyclists are female, and that 48% find Copenhagen `good' or `excellent' for cycling. The satisfaction with the maintenance of cycle tracks and streets is much smaller, which has made the municipality increase its activities—and the budget—for cycle track maintenance. DKK 9.1 million (€1.2 million or £0.75 million) was set aside for maintenance in 2000. The key figures from the most recently published Bicycle Account (2000) are shown. The Bicycle Account can be found on the Internet and is also available in print [38]. Other publications describe the bicycle strategies of Copenhagen in more detail [66].

|

[pp. 232-233,235]

He has a lengthy description of their CityBike project, a free bike project within the city centre with a deposit of DKK 20 (€2.70 or £1.70). He is largely negative on the project, due to theft and vandalism issues and difficulty finding any private sector support or even advertising interest. His final note is that:

An investigation has shown that the bikes are used primarily by tourists and young men, most trips lasting just 5-10 minutes. It seems that less than 10% of the fleet is available in the racks, meaning that a good many must have left City Bikes elsewhere than in the designated racks. Compared to the number of people cycling on private bicycles, the City Bike adds virtually nothing to the cycle traffic of Copenhagen.

[p. 235]

Traffic calming on the national road network to improve cycling conditions in small towns in Poland: the case of Kobylnica Slupska on National Road 21 [74]

Most of this chapter is devoted to a discussion of a single traffic calming project, which happened to include bicycle lanes. It's not too relevant overall, but there's some interesting Polish trivia.

In the 1980s the bicycle was perceived as an element of anti-socialist activities and cycle infrastructure was not implemented.

[p. 237]

Individual motorisation grew rapidly from 112 cars per 1000 people in 1990 to 258 cars per 1000 people in 2000

[p. 238]

It must be noted that in Poland parking cars on the footway is permitted!

[p. 238]

[D]uring the year 1988-1992, 29 accidents were recorded, in which 11 pedestrians were killed or injured. [...] Average speeds through the village were reduced from nearly 70 km/h before to 48 km/h in 1995 and 44 km/h in 2001. [...] Average journey time through Kobylnica increased from 24 seconds to 41 seconds. [...] The safety level for all road users was improved significantly; within one year of the reconstruction fatal accidents disappeared and only one injury accident was recorded.

[pp. 241, 246, 247]

The traffic calming scheme has withstood its winter tests well. The cycle paths then change their functions. During the winter they are used for storing snow.

[p. 247]

Padua: a decade to become a cycle city [46]

Nothing exceptional in this chapter.

Cyclists' and pedestrians' journeys can never fit rigid origin-destination patterns and their freedom of movement must be supported and increased.

[p. 254]

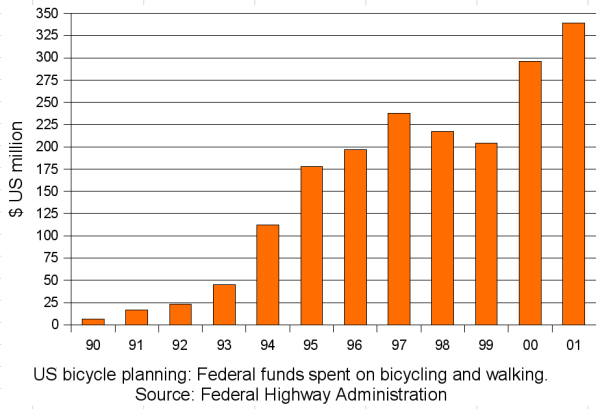

US bicycle planning [7]

Despite massive increases in federal funding during the 1990s, the US has seen very little increase in ridership: from 467,000 in 1990 to 567,000 in 2000 [pp. 264, 265].

Although there has been tremendous progress in the planning and design of roadways to accommodate bicyclists, there are still significant gaps in such areas as the accommodation of bicyclists at intersections; the safety of bicyclists at roundabouts; and the use of coloured pavement (carriageway) markings, bicycle signal heads and other bicycle specific traffic control devices. The results of decades of experience from European and other countries (e.g. Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Australia, China) remain untried in the United States because of a lack of access to foreign language research and an unwillingness to accept `other people's' solutions.

[p. 270]

Bicyclists are over-represented in crash statistics, yet safety improvements for bicyclists have historically received little funding or attention. Bicyclists and pedestrians together account for 14% of traffic fatalities, only 7% of trips, and less than 1% of safety-related construction funds.

[p. 271]

Increasing cycling through `soft' measures (TravelSmart)—Perth, Western Australia [1]

The traditional approach to changing community behaviour, especially in the health promotion area, is social marketing [4]. However, there is little evidence that traditional social marketing campaigns based on the health promotion model are effective at changing individuals' travel behaviour. Brög argues traditional social marketing focused on target audiences is not appropriate to change travel behaviour on the basis that:

- People's travel decisions are based as much on their environment as their attributes

- People's misperceptions of cycling and public transport are best improved through direct experience of the modes; and

- People need help to identify which trips can be used by alternative modes, which is different for each household and each household member.

Individualised Marketing, a specialised dialogue marketing technique developed by Socialdata, establishes direct contact with individuals to take them through a process that identifies the real demand for information and motivates them more easily to think about and change their behaviour.

[p. 277]

The results of this assessment of the pilot programme demonstrated a 15:1 benefit-cost ratio [37]. The 15:1 estimate is now considered to be an underestimate because it was based upon rapid decay of the behaviour change benefits, a scenario that is now evidenced to be incorrect. Traditionally, transport projects require significant building of roads and infrastructure. They usually have a benefit-cost ratio in the range of 2:1 up to 7:1.

[pp. 286-287]

Bibliography

- 1

-

Colin Ashton-Graham, Gary John, Bruce James, Werner Brög, and Helen

Grey-Smith.

Increasing cycling through `soft' measures (TravelSmart)—Perth, Western Australia.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 18, pages 274-289. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 2

-

Wolfgang Bohle.

German cycling policy experience.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 13, pages 209-222. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 3

-

T. Bracher, H. Luda, and H.-J. Thiemann.

Zusammenfassende Auswertung von Forschungsergebnissen zum Radverkehr in der Stadt.

Technical report, Forschung Stadtverkehr, Bundesministerium für Verkehr (Federal Ministry of Traffic), Band A7, Bergisch Gladbach/Berlin/Bonn, Germany, 1991. - 4

-

Werner Brög, E. Erl, S. Funke, and B. James.

Behaviour change and sustainability from individualised marketing.

In Proceedings of 24th ATRF Conference, Perth, Australia, September 1999. - 5

-

I.C. Cameron, N.J. Harris, and N.J. Kehoe.

Tram-related injuries in Sheffield.

Injury, 32(4):275-277, May 2001. - 6

-

Centre for Research and Contract Standardisation in Civil Engineering (CROW).

Sign up for the bike: design manual for a cycle-friendly infrastructure.

Technical report, CROW, Ede, The Netherlands, 1993. - 7

-

Andy Clarke.

US bicycle planning.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 17, pages 263-273. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 8

-

Jo Cleary.

Developing healthy travel habits in the young: Safe routes to school in the UK.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 6, pages 86-99. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 9

-

Jo Cleary and Hugh McClintock.

Evaluation of the Cycle Challenge Project: A case study of the Nottingham cycle-friendly employers' project.

Transport Policy, 8(2):117-125, April 2000. - 10

-

Jo Cleary and Hugh McClintock.

The Nottingham cycle-friendly employers' project: lessons for encouraging cycle commuting.

Local Environment, 5(2):217-222, 2000. - 11

-

Cleary Hughes Associates.

Nottingham Cycle Challenge Project: Final report.

Technical report, Cleary Hughes Associates, Hucknall, Nottingham, UK, 1999. - 12

-

Nigel Coates.

Parking policy and bicycle promotion in Oxford.

In Proceedings of Velo-City 1997, Barcelona, Spain, September 1997. - 13

-

Commission for Integrated Transport.

European best practice in delivering integrated transport.

Technical report, Commission for Integrated Transport, London, UK, November 2001. http://www.cfit.gov.uk/docs/2001/ebp/index.htm - 14

-

S. Cullinane.

Attitudes towards the car in the UK: some implications for policies on congestion and the environment.

Transportation Review, 26A:291-301, 1992. - 15

-

Cyclists' Public Affairs Group.

BikeFrame: A model cycling policy.

Technical report, Cyclists' Touring Club and the Bicycle Association, Godalming, UK, 2001. - 16

-

D. Davies.

Light rapid transit: implications for cyclists.

Technical report, Cycle Touring and Campaigning, June/July 1989. - 17

-

D.G. Davies and E. Hartley.

New cycle owners: Expectations and experience.

Technical Report 369, Transport Research Laboratory Limited, London, UK, 1999. - 18

-

Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions.

A road safety good practice guide.

Technical report, Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions, London, UK, 2001. http://www.roads.dtlr.gov.uk/roadsafety/goodpractice/18.htm - 19

-

DSB (Danish State Railways).

Cykelparkering og cykelcentre: et idekatalog (Cycle parking and cycle centres: a catalogue of ideas).

Technical report, DSB Styregruppen vedr. cykelparkering, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1990. - 20

-

DSB (Danish State Railways, S-Togsdivision).

Handlingsplan for forbedring af cykelparkering ved S-stationer (Plan for promotion of cycle parking at S-train stations).

Technical report, DSB Styregruppen vedr. cykelparkering, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1991. - 21

-

D. Alrutz et al.

Begleitforschung Fahrradfrendliche Städte und Gemeinden NRW: Maßnahmen- und Wirksamkeitsuntersuchung.

Technical report, Ministerium für Wirtschaft und Mittelstand, Energie und Verkehr NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany, 2000. - 22

-

R. Field.

Are you being squeezed at road narrowings?

Technical report, Cyclists' Touring Club, Godalming, Surrey, UK, 2001. - 23

-

T. Froitzheim.

Fahrradstationen an Bahnofen: Modelle, Chancen, Risiken.

Technical report, ADFC-Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1990. - 24

-

John Grimshaw.

The UK National Cycle Network: a millenium project.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 7, pages 100-109. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 25

-

N. Guthrie, D.G. Davies, and G. Gardner.

Cyclist's assessments of road and traffic conditions: the development of a cyclability index.

Technical Report 490, Transport Research Laboratory Limited, Crowthorne, UK, 2001. - 26

-

S. Hanaoka.

Present bicycle traffic situation in Japanese cities.

In Proceedings of Velo-City 1997, Barcelona, Spain, September 1997. - 27

-

A. Hanton and S. McCombie.

Provision for cycle parking at railway stations in the London area.

Technical report, London Cycling Campaign, London, UK, 1989. - 28

-

James Harrison.

Planning for more cycling: the York experience bucks the trend.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 9, pages 143-154. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 29

-

Mayer Hillman.

Cycling: Towards health and safety.

Report of a BMA working party, British Medical Association, Oxford, UK, 1992. - 30

-

Mayer Hillman, J. Adams, and J. Whitelegg.

One False Move... A study of Children's Independent Mobility.

PSI Publishing, London, UK, 1990. - 31

-

Dave Holladay.

Cycling with public transport: combined in partnership, not conflict.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 8, pages 110-142. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 32

-

T. Hughes.

Exploring Nottinghamshire by bike.

Countryside Recreation, 8(3), August 2000. - 33

-

Institution of Highways and Transportation.

Guidelines for cycle audit and review.

Technical report, IHT, London, UK, 1998. - 34

-

Institution of Highways and Transportation, Bicycle Assocation, and

Cyclists' Touring Club.

Cycle-friendly infrastructure: Guidelines for providing and design.

Technical report, IHT, London, UK, 1996. - 35

-

Søren Underlien Jensen.

DUMAS: Safety of pedestrians and two-wheelers.

Note 51, Vejdirektoratet, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. - 36

-

M. Jones.

Promoting cycling in the UK: Problems experienced by the practitioners.

World Transport Policy and Practice, 7(3):7-12, 2001. http://www.eco-logica.co.uk/wtpp07.3.pdf - 37

-

I. Ker and B. James.

Evaluating behaviour change in transport: Benefit cost analysis of individualised marketing.

Technical report, Transport WA, Perth, Australia, 1999. - 38

-

Københavns Kommune (Municipality of Copenhagen).

Cykelregnskab 2000 (Bicycle Account 2000).

Technical report, Københavns Kommune, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. http://www.vejpark.kk.dk/publikationer/pdf/156_CykelregnskabDK.pdf - 39

-

E. Koop.

On the recent engagement of bicycles and trains in Denmark.

In N. Jensen, editor, Proceedings of Velo-City 1989, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1990. - 40

-

Thomas Krag.

Urban cycling in Denmark.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 14, pages 223—236. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 41

-

C. Kuranani and D.D. Bel.

Bicycle parking in Tokyo: Issues, policy and innovation.

In Presented at the 76th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C., USA, 1997. - 42

-

S. Lawson and B. Morris.

Our of cars and onto bikes: what chance?

Traffic Engineering and Control, 40(5), May 1999. - 43

-

Todd A. Litman, Robin Blair, Bill Demopoulos, Nils Eddy, Anne Fritzel, Danelle

Laidlaw, Heath Maddox, and Katherine Forster.

Pedestrian and bicycle planning: A guide to best practices.

Technical report, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. http://www.vtpi.org/nmtguide.doc - 44

-

A. Luers.

Reiseantrittwiderstande, speziell der Einfluss wohnungsnaher Abstellmöglichkeiten auf den Verkehrsanteil des Fahrrades (Resistance factors at the start of journeys, with particular reference to the availability of cycle parking facilities near residences).

In Perspektiven des Fahrradverkehrs: Internationaler Planungsseminar auf Schloss Laxenburg bei Wien, Vienna, Austria, 1985. - 45

-

H. Maddox.

Another look at Germany's bicycle boom: implications for local transportation policy and planning strategy in the USA.

World Transport Policy and Practice, 7(3):44-48, 2001. http://www.eco-logica.co.uk/wtpp07.3.pdf - 46

-

Marcello Mamoli.

Padua: a decade to become a cycle city.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 16, pages 251-262. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 47

-

D. Mathew.

New way ahead for Oxford: a balanced transport policy.

Surveyor, 175(5126):16-17, October 1990. - 48

-

C.T. Matwie and J.F. Morrall.

Guidelines for a safety audit of bikeway systems.

World Transport Policy and Practice, 7(3):28-37, 2001. http://www.eco-logica.co.uk/wtpp07.3.pdf - 49

-

Hugh McClintock.

Cycle facilities and cyclists' safety: experience from Greater Nottingham and lessons for future cycling provision.

Transport Policy, 3(1/2), January 1996. - 50

-

Hugh McClintock.

The development of UK cycling policy.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 2, pages 17-35. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 51

-

Hugh McClintock.

The mainstreaming of cycle policy.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 1, pages 1-16. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 52

-

Hugh McClintock.

Nottingham.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 11, pages 171-191. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 53

-

Hugh McClintock, editor.

Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners.

Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 54

-

Hugh McClintock.

Promoting cycling through `soft' (non-infrastructural) measures.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 3, pages 36-49. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 55

-

Hugh McClintock and Jo Cleary.

English urban cycle route network experiments: the experience of the Greater Nottingham network.

Town Planning Review, 64(2):159-192, 1993. - 56

-

Hugh McClintock and V. Shacklock.

Alternative transport plans: encouraging the role of employers in changing staff commuter travel modes.

Town Planning Review, 67(4), October 1996. - 57

-

Ministry of Transport.

Traffic in towns: A study of the long term problems of traffic in urban areas (Buchanan report).

Technical report, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, UK, 1963. - 58

-

Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management.

Sustainable road safety programme.

Technical report, Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1997. - 59

-

National Cycling Forum.

Cycling in urban areas: issues in retailing.

Technical report, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, London, UK, 1998. - 60

-

National Cycling Forum.

Model conditions of carriage: Accommodating the bicycle on bus and coach.

Technical report, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, London, UK, 2001. - 61

-

Nottinghamshire County Council.

School travel: Health and the environment.

Technical report, Nottinghamshire County Council, Nottingham, UK, 1995. - 62

-

Organisation for Economic Co operation and Development.

Safety of vulnerable road users.

Technical report, OECD, Paris, France, 1997. - 63

-

Stuart J. Reid.

Pushing bikes.

Surveyor magazine, pages 18-20, June 2001. - 64

-

A. Russell.

Selling the cycle habit.

Surveyor magazine, October 2000. - 65

-

Graham Paul Smith.

Homezones and traffic calming: implications for cyclists.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 5, pages 72-85. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 66

-

M. Thomas.

Copenhagen city of cyclists.

Technical report, Municipality of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1997. - 67

-

Transport 2000 Trust.

A safer journey to school: A guide for school communities.

Technical report, Transport 2000 Trust, London, UK, 1999. - 68

-

J. Tschopp.

Bike and ride and the introduction of the green reduction card: Basle, a success story in stimulating use of public transport and the bike.

In Proceedings of Velo-City 1987, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1988. - 69

-

Mark Wardman, R. Hatfield, and Matthew Page.

The UK national cycling strategy: Can improved facilities meet the targets?

Transport Policy, 4(2):123-133, 1997. - 70

-

A.G. Welleman.

The Netherlands national cycling policy and facilities for cyclists at signalled junctions.

paper given to meeting, The Local Authorities Cycle Planning Group, York, UK, May 1991. - 71

-

Ton Welleman.

An efficient means of transport: experiences with cycling policy in the Netherlands.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 12, pages 192-208. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 72

-

P. Wramborg.

On a new approach to urban planning, traffic network and street design with a special focus on bicycling.

In Proceedings of Velo-City 99, Graz, Austria, 1999. ftp://kamen.uni-mb.si/velo-city99/proceedings.pdf - 73

-

Michael Yeates.

Making space for cyclists: a matter of speed?

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 4, pages 50-71. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002. - 74

-

Andrzej Zalewski.

Traffic calming on the national road network to improve cycling conditions in small towns in Poland: the case of Kobylnica Slupska on National Road 21.

In Hugh McClintock, editor, Planning for Cycling: Principles, Practice and Solutions for Urban Planners, chapter 15, pages 237-250. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, UK, 2002.